Ari is a wog.

Ari is a

faggot.

Ari is

Greek but not Greek.

Australian

but not Australian.

Running but

not getting anywhere.

He shits,

pisses, fucks and dances. He’s Persephone, struck by the melodies of Kanye and

the Jackson Five. Of M.I.A. and Beyonce.

Ari spends

half his time in hell and he’s beginning to like it there.

Ari is the

lead character of Christos Tsiolkas’ iconic 1995 Melbourne-set novel, Loaded,

which was adapted into a film (Head On, 1998) by director Anna Kokkinos and fellow playwright,

Andrew Bovell. It was through this film adaptation that drew Tsiolkas to the

Melbourne Workers Theatre and the creation of the classic Australian play, Who’s Afraid of the Working Class, written by Tsiolkas, Bovell, Patricia

Cornelius and Melissa Reeves.

Since Loaded,

Tsiolkas has written eight novels and a number of plays. His short story

collection, Merciless Gods, was adapted into a play by Dan Giovannoni

several years ago, in conjunction with theatre company, Little Ones, a group which

included director Stephen Nicolazzo.

Through the

alchemy of Tsiolkas’ original novel, his and Giovannoni’s adaptation and

Nicolazzo’s superb direction, Loaded opened last night to rapturous

applause at the Malthouse Theatre.

Originally

programmed for 2020, the play was cancelled due to the pandemic and was then

fashioned into an audio drama, which is still available to listen to. But now

that the world is more or less back to whatever constitutes normal these days, Loaded

is finally on stage and Ari is ranting about the state of his world all over

again.

The novel

is confronting and the film is bleak. Ari is clear-eyed in his nihilism, never

wavering from his determination never to be defined. He goes from moment to

moment looking for the next hit, the next score. Pure, unadulterated hedonism.

The

creative team behind this production chose early on to set this stage version

now, in present day, though there’s not a mention of the pandemic that stopped

the show. Perhaps, rather than being a period piece set in the 1990s, Loaded

is a pre-pandemic play, set in the halcyon days of 2019.

It was

strange to hear text from the original novel sprinkled with modern day

references at the start. This teenage boy was mostly obsessed with musicians of

the past or his early childhood; hearing Ari rattle off the tracks from Kanye’s

Yeezus album was a little startling.

But the

novel is a time capsule now. It describes a Melbourne that no longer exists. At

one stage Ari takes a train into the city and jumps off at Princes Bridge

station, which closed in 1997. (The Melbourne skyline in the 1998 film is almost

unrecognisable now!)

In a story

where the main character refuses to change, this new play charts how much the

city of Melbourne has changed in the nearly thirty years since the novel was

first written. Tsiolkas and Giovannoni’s adaptation is all the stronger for looking

forward because if you look back, Ari warns, you might disappear.

The novel

reads like a monologue. Even though other characters get to speak, it is Ari

relating the story to us. His thoughts and feelings always close to the

surface, ready to dart in whenever anyone else finishes speaking or takes a

breath. We are in his experience always; devising the show for a solo actor is

the only thing that makes sense.

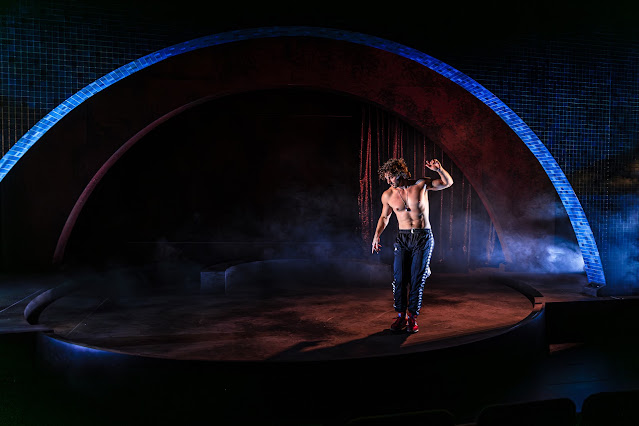

Actor Danny

Ball is captivating as Ari, bringing to life words written so long ago that

echo through the decades. In the opening scene of the book, his brother’s

housemates are lost in their thoughts or reading a newspaper. Now, they are

staring at their phones. The only thing Ari wants a phone for is to stream

music, popping on a pair of headphones that put the Walkman ones in the novel

to shame.

Ball grabs

the audience from moment one; beyond the poetry of the text, he uses his

physicality to create a brutal force one moment and a subtle gracefulness in

the next. He must embody Ari’s raw sexuality but also convey Jonny’s evolution

into Tula and an exquisite moment of her dancing on the stage at The 86. But

just as in the book, it’s always Ari telling these other people’s stories –

even when they have their moment to shine, Ari is quick to snuff them out if he

wants to move on somewhere else. Ball is extraordinary throughout.

The set by

Nathan Burmeister is deceptive in its simplicity. A dank dark wall at the back.

A blue-tiled arch at the front. A revolve in the centre of the stage shows how

fast Ari is running from things and how quickly he can slide toward temptation.

A curtain of coloured streamers evokes house parties and nightclubs – coming and

going as quickly as Ari does.

Katie

Sfetkidis’ lighting works perfectly in concert with Burmeister’s set, creating

much tension in the alleys and houses and streets Ari wanders down or

disappears into. Sometimes it’s painterly and evocative; sometimes it’s just

shiny and hard or the deepest of blacks.

This Ari

rails against his uni wanker mates and their obsession with race and gender identities.

One of them wants to talk about class, too, but that seems forgotten – a mirage

like the ghost Ari feels himself to be. But dropping Ari into modern day, where

one of the key political discourses is about intersectionality, the adaptation puts

the character in a whole different light to the one that shone on him in the

mid-90s.

I imagine young

Greek men still struggle to come out to their families. But if we look at Ari

through the lens of intersectionality, then we see a story that feels very now.

In the novel, he lived in a world where his different identities were always in

conflict. Might current views help him to reconcile the many different facets he

contains? Or is Ari destined to be lost whatever decade he wakes up in?

Early on, I

wondered if the changing face of Melbourne might dilute the power of Ari’s

story. As immigrants are pushed further and further from the inner city, I wondered

if Ari’s wild night out might be stretched thin. And could the power of the

novel still be held now, in a world where queer storytelling has become more

mainstream? But no, of course, since queer storytelling is always under threat,

the boldness of Tsiolkas’ dramatic, confronting, unapologetic trip through the

city and the suburbs has lost none of its richness and vitality.

Stephen

Nicolazzo’s direction is precise, thoughtful and fearless. After a career of

queering texts and embracing camp (and helming an incredible adaptation of Looking

for Alibrandi last year), he’s taken another modern classic and put it on

stage like the story always wanted to be there. Like Ari broke out of the pages

and demanded to be listened to again. Proving that it’s still a tale worth telling.

On the page. On film. And at the Malthouse.

Loaded is packed with a stunning central

performance, incredible work from two writers from different generations, and fashioned into

a production that must not be missed.

It’s already

selling so well, the season has been extended by a week.

- Keith Gow, Theatre First

Loaded and Ari are running at the Malthouse until June 3.

Photographs: Tamarah Scott

Comments