|

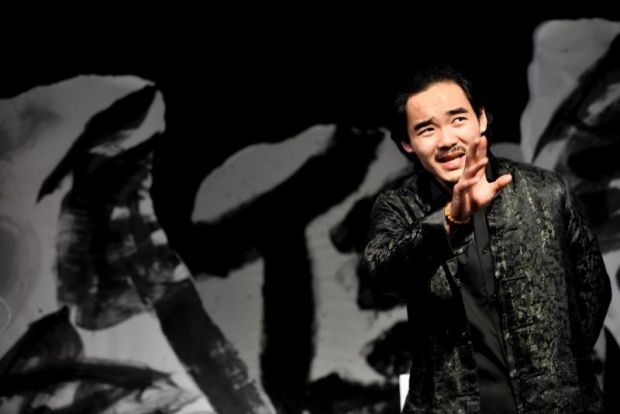

| Louis Le in Caught at Red Stitch |

As we walk from the foyer toward the pop-up gallery and performance space, along the walls of the corridor are works by Chinese artist and dissident, Lin Bo. We take our seats under the full house lights and we are welcomed and warned that Lin’s work is challenging and that if anyone needs to discuss what they see, a staff member will be available to talk with us later.

Lin Bo

arrives to great applause and he talks about art in China, the 798 District in

Beijing and explains his plan for an “imaginary protest” he organised in memory

of the June Fourth incident at Tiananmen Square. And though his performance art

amounted to nothing, his seeding the idea of a protest amongst the population

was enough to pique the interest of the Chinese Government. He was held in

detention for two years, subsisting on cabbage soup, living in a cell that was

exposed to the elements.

Lin was

recently profiled in the New York Times and he is writing a memoir, to be

published next year by Simon & Schuster. It was a real treat to hear him

speak about his work and his harrowing time in prison. It made me feel very

privileged that I don’t make political art while living in a dictatorship. His

introduction to his work was very moving.

And

everything I have told you above is a lie.

*

You’re

reading a review of a play. Your expectations have been set. In this medium, you

know I’ll outline the basic premise of the play and then tell you what I liked

and disliked about it.

You know

from the title of this post it’s the review of a play titled Caught by a

writer named Christopher Chen. If you’ve ever been to Red Stitch, you know the

corridor between foyer and theatre. And if you haven’t, you can imagine it. And

you can guess, from what I’ve told you above, it’s a little bit immersive.

The

audience is walking into a performance space playing a pop-up gallery space

that later turns out to also be a performance space. But we’re not there yet.

Before

that, before Lin can have his memoir published and continue his publicity tour,

we need to understand more about his experiences and his truth. Has he taken

some dramatic licence with the story of his life? Are we treading into James

Frey territory or, perhaps, into the theatrical stylings of Mike Daisey?

Christopher

Chen wants you to question everything.

*

In a world

that is increasingly post-truth, where large swathes of people across the world

are choosing to believe whatever makes them most comfortable, Chen’s play wants

to deconstruct the truth of the play the audience is watching as we are

watching it. Lin Bo might have been a real artist, but we’re in a theatre, so

we’re expecting fiction and flights of fancy. We know we’re in a theatre not a

pop-up gallery, but we’ve been trained – over years of engaging with live

performance – to put that truth aside for a while.

The stories

Lin tells about Chinese prisons, though; they sound real. That fits in with our

pre-conceived Western notions about how China treats its citizens. We’ve seen

the photo of a lone protestor standing in front of a tank on June 4th,

1989 – and we know that photograph is banned in China. We are happy to believe

in the veracity of this monologue. Even though we know we are watching a play.

And then

the rug is pulled out from under us.

Over and

over and over again.

The

production alludes to the kind of immersive theatre where our collective

unconscious dreams us into a fictional place, even though – in this case – we

are just sitting in a seating bank.

The real

immersion turns out to be in how our brains engage with what we are watching,

as each scene recontextualises the scene before. We are caught in Caught.

*

Jean Tong’s

production of this exciting, challenging and mind-bending work is incredibly

effective – lulling the audience into traps, allowing us to engage with

characters while knowing we are being played with. The text asks a lot of the

actors, but it needs a director with a clear vision. Tong guides the cast

through a play that is boxes within boxes within boxes. We’re on the outside

looking in and the inside looking out; sometimes both at the same time.

The entire

ensemble is excellent, although the stand-out is Jing-Xuan Chan, holding the

audience in the palm of her hand, while her character (or characters?) poke and

prod our brains with questions of truth, intentionality and cultural

appropriation. In moments, she is relaxed and charming and, at other times,

she’s as clearly manipulative as a cult leader. A stunning performance.

Because the

play is built on obfuscation and surprise, it’s hard to talk about some of the

later dramatic reveals. It feels exciting to be in the hands of theatre-makers

so in control of their craft.

Caught is a tricky play, slippery, hard to

grasp and so compelling. It asks a lot of its audience, as good theatre must,

but it will drag you through the wringer, only to arrive at difficult answers

and leave you with a lot of questions.

This is thrilling, complicated, challenging theatre. Highly recommended.

- Keith Gow, Theatre First

Caught runs until September 11 at Red Stitch Actors Theatre.

Photograph: Jodie Hutchinson

Comments